Explore

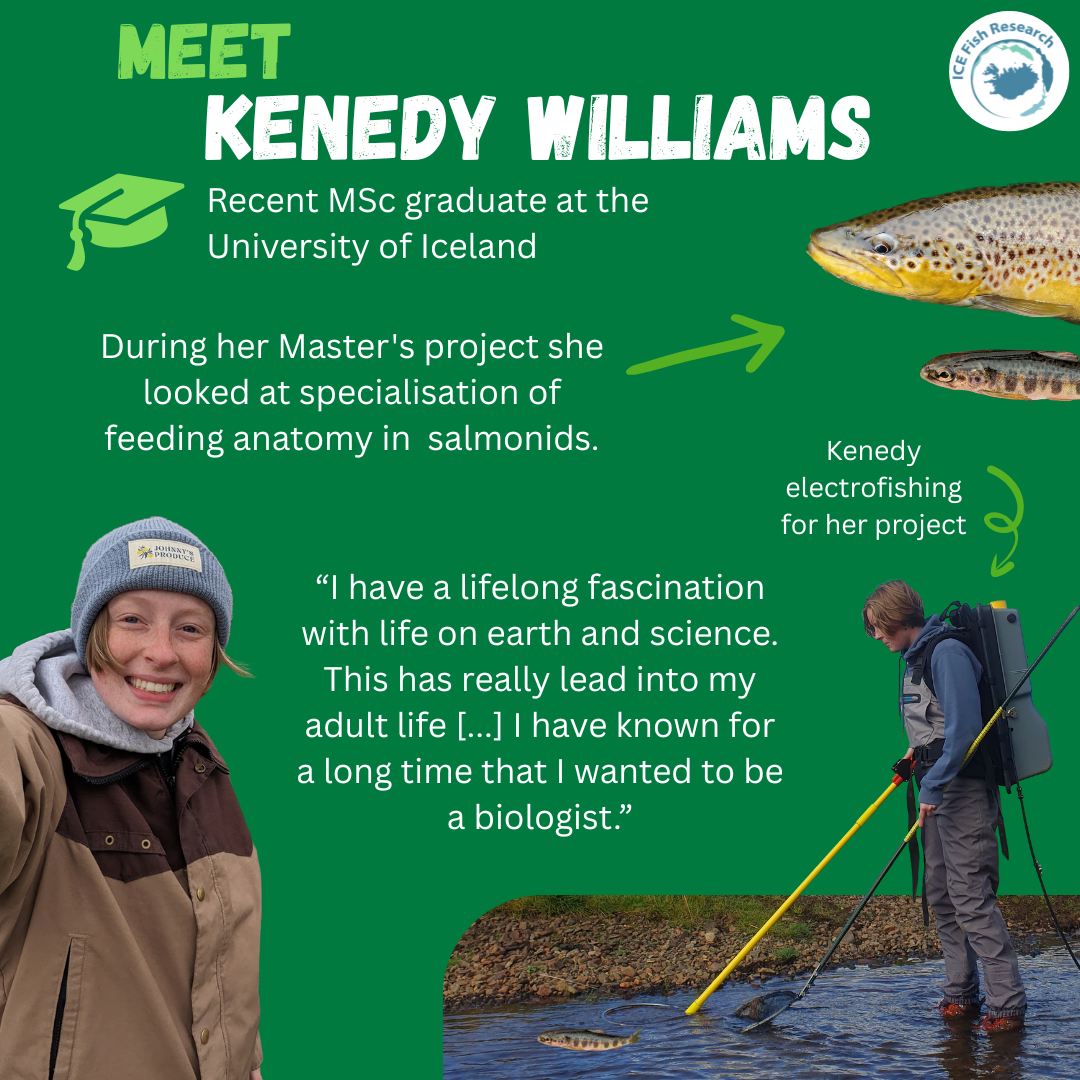

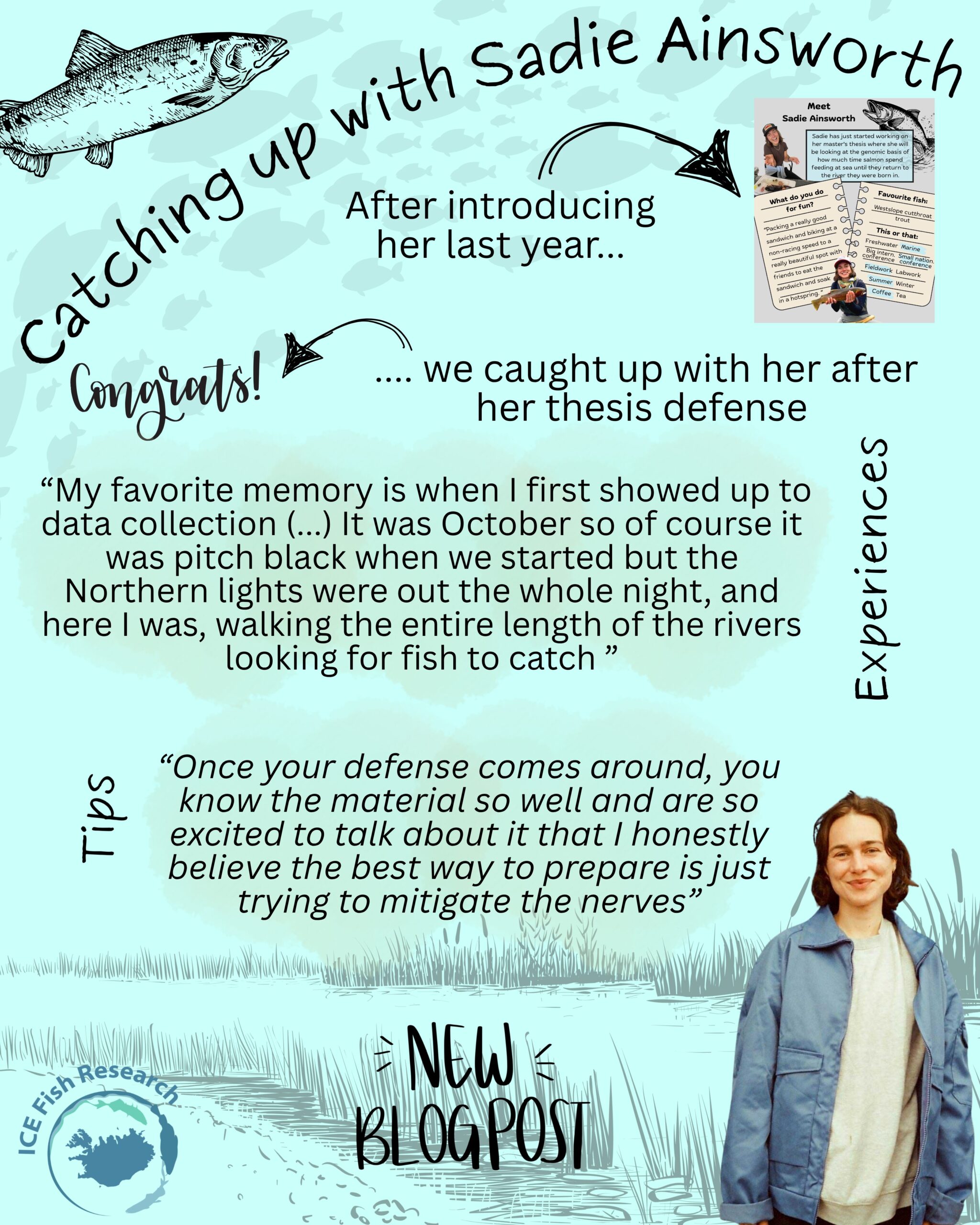

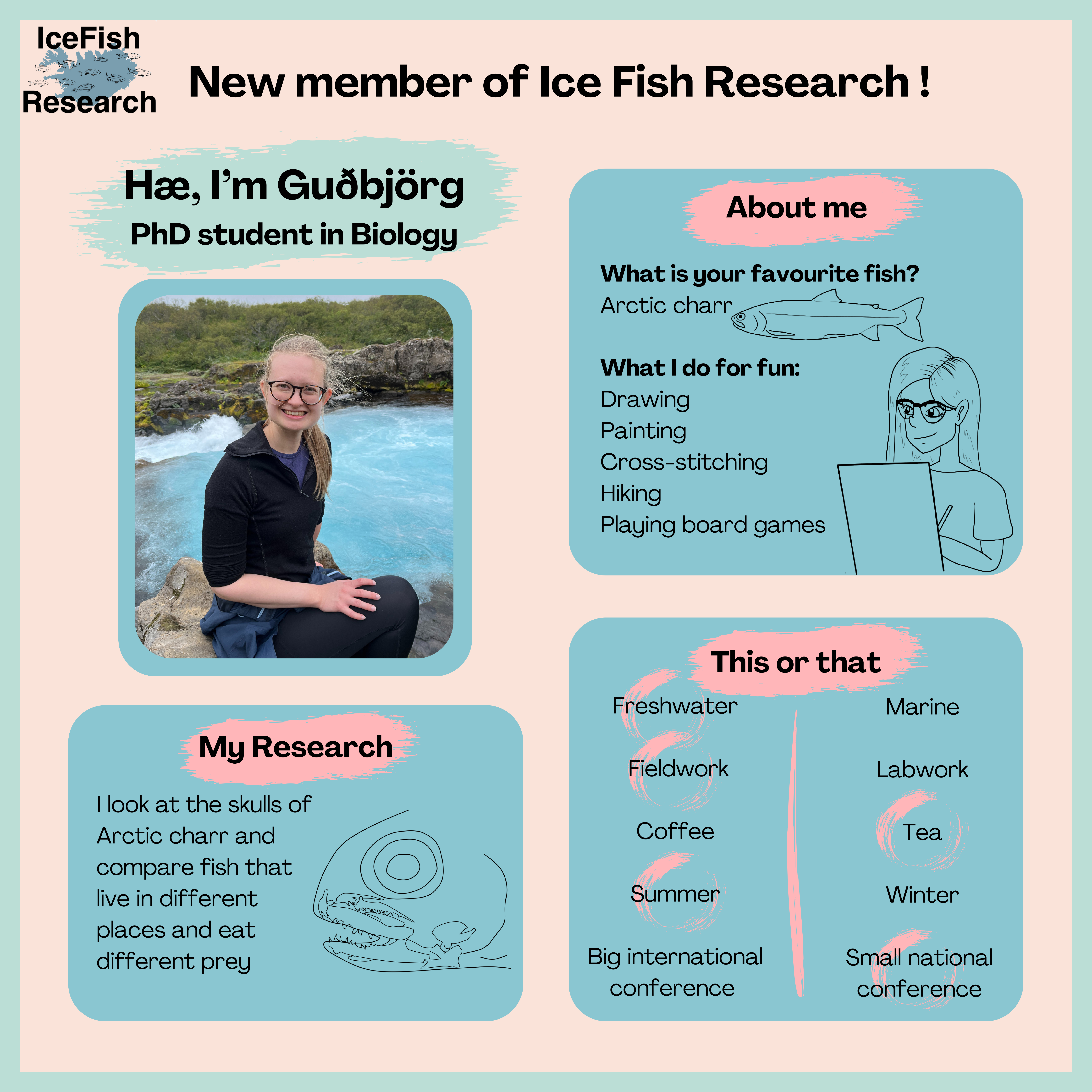

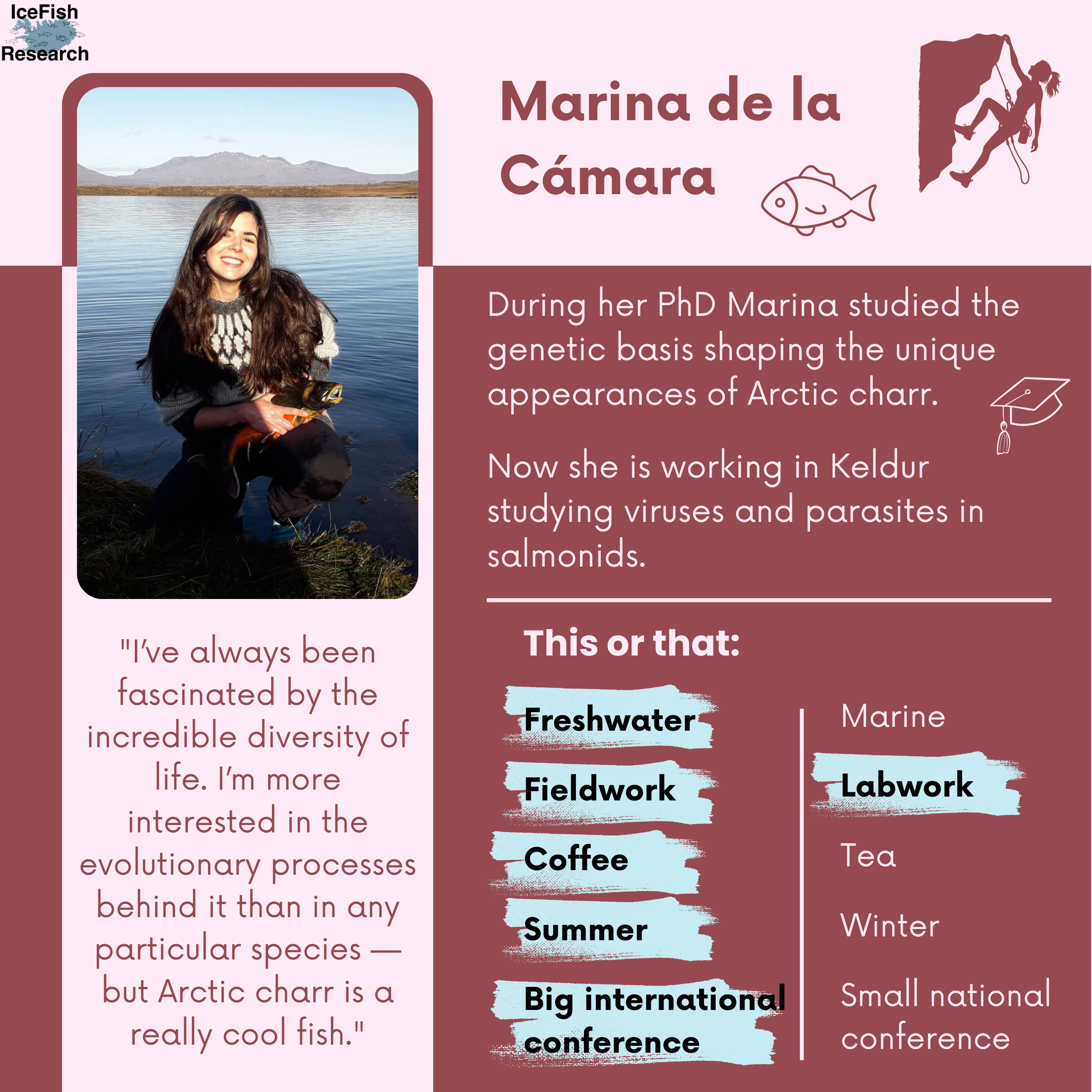

Scientist spotlight

Meet the scientists behind fish research in Iceland and find out what it really is like to be a scientist.

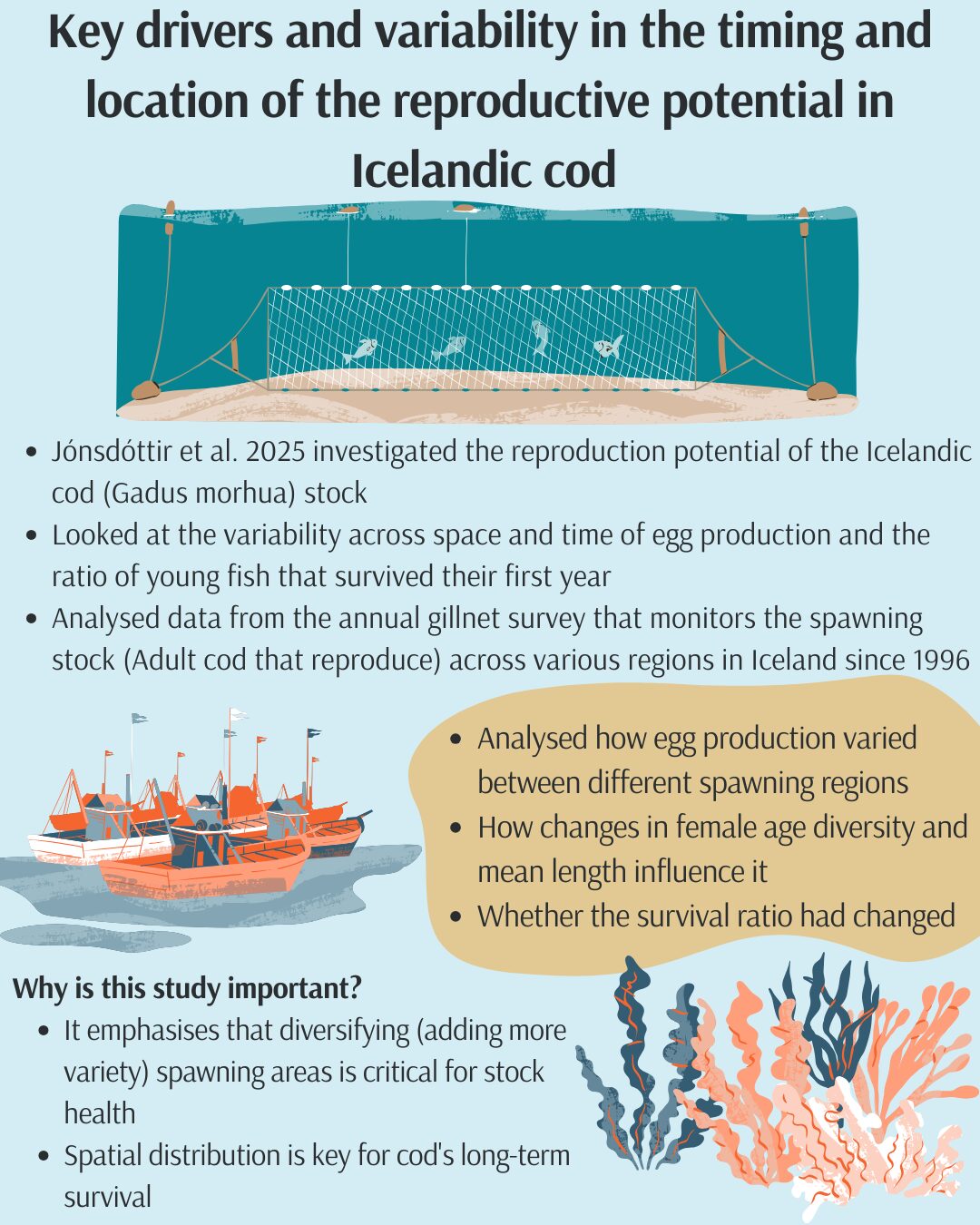

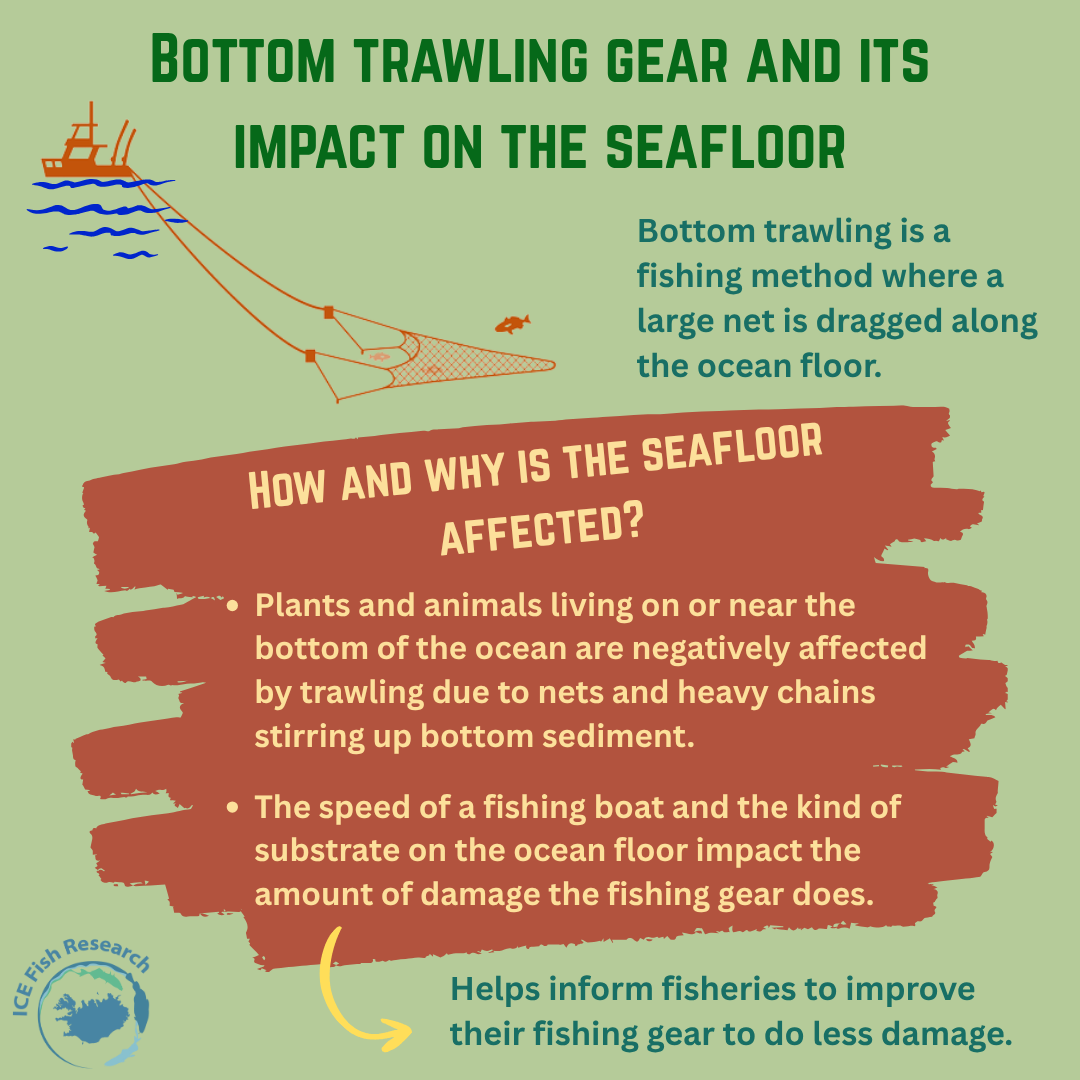

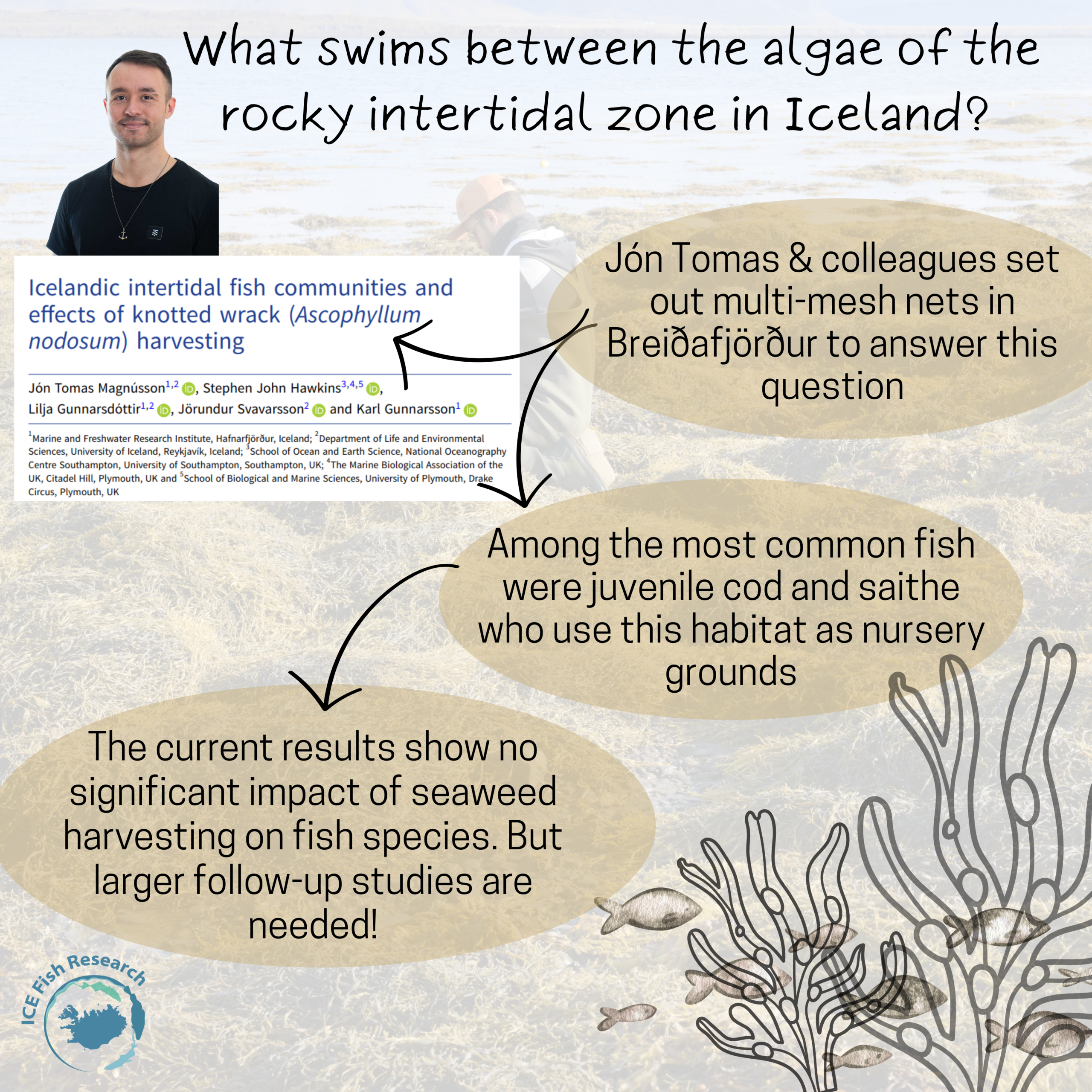

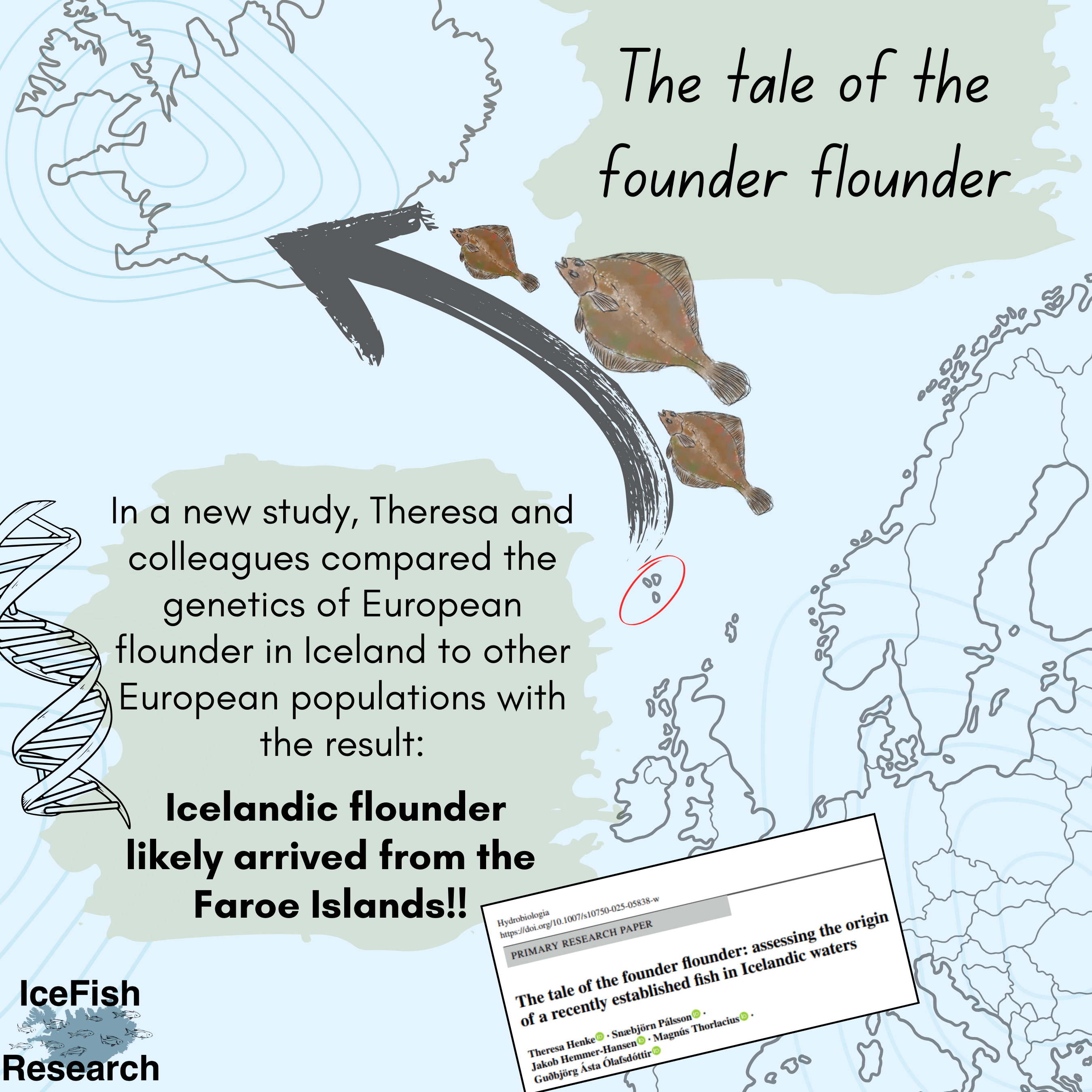

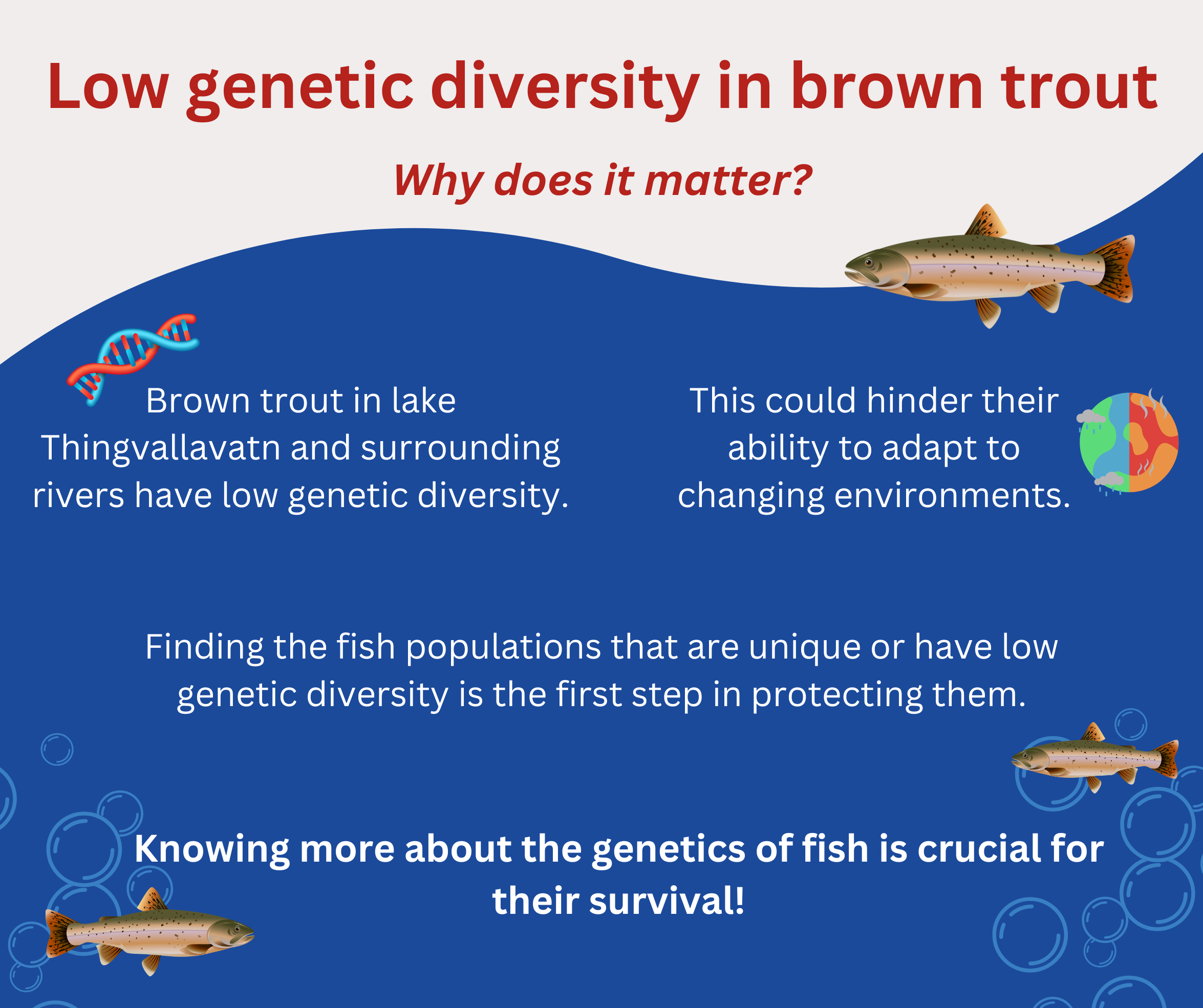

Publications

Learn more about past and present research on fish in Iceland. Not to worry, we do it in a fun and simple way.

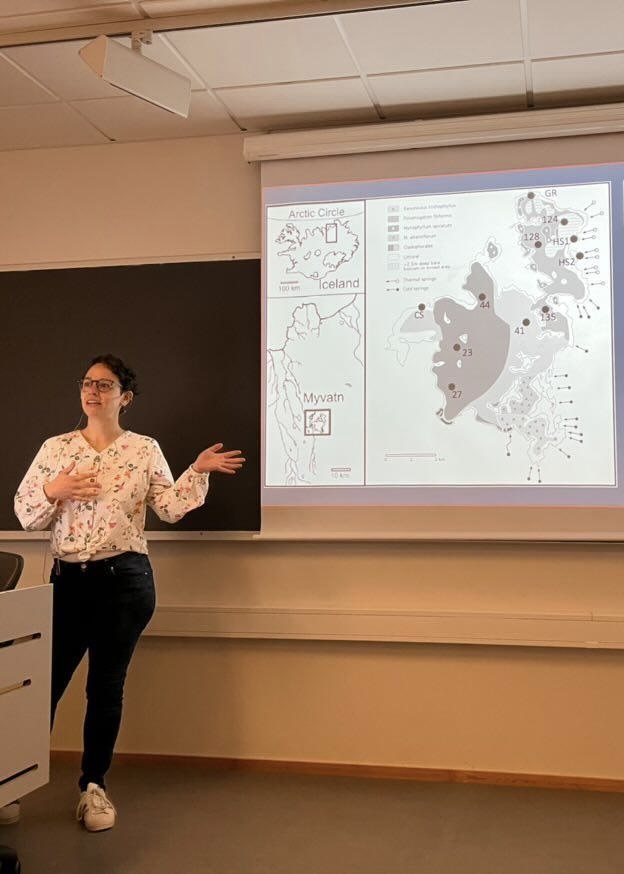

Discovery zone

Explore what is happening in the world of Icelandic fish. Stories about citizen scientists, running projects and more!

ABOUT US

We want to make research on fish in Iceland available to everybody.

We hope that our passion will reach people across Iceland and inspire you to connect through fish science.

We highlight researchers who are just getting started and motivate them to share their work with young and old.

Hopefully, this will inspire especially young people to be curious and ask questions.

SHARE YOUR SCIENCE

Are you a researcher working on or someone passionate about Icelandic fish and want to share who you are and/or what you do? Contact us!